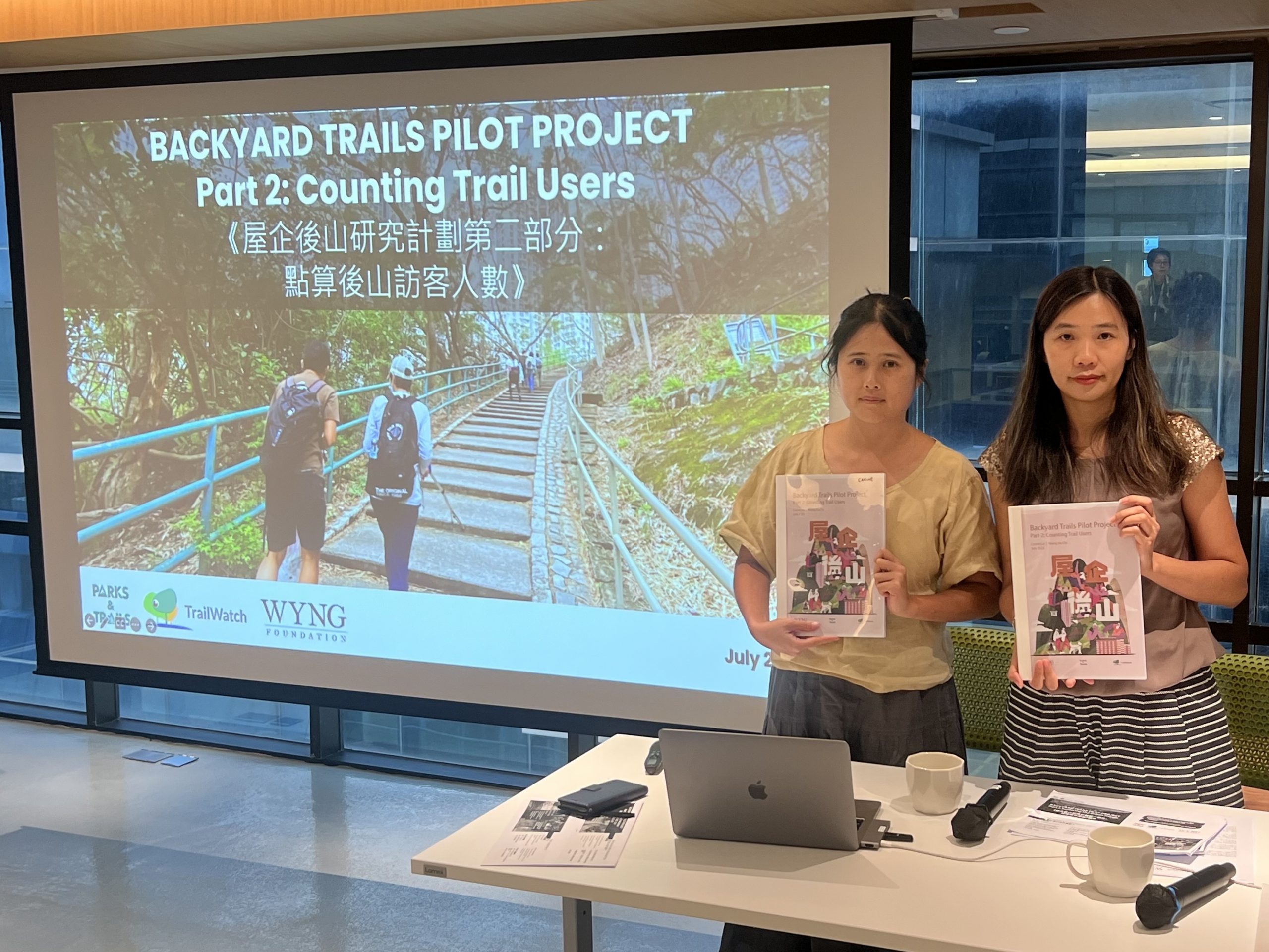

In early April, we released the report of “Backyard Trails Pilot Project Part 1: Exploring the Urban Fringe”, a preliminary qualitative analysis of the recreational value of eleven selected backyard trails mapped with TrailWatch App to gain a more detailed understanding of their present condition.

The report also spells out the strategies of repairing and achieving long-term cooperative backyard trail management.Backyard trails are not administered as urban parks nor do they belong to country parks, hence they are given a low priority in open space planning and recreational policy. However, the research estimated that approximately 1.5 million residents live within 15 minutes’ walking distance of the eleven trails altogether, constituting 20% of Hong Kong’s population. Backyard trails function as an important green lung.

Sum Kwong, Partnership and Communications Head of Parks and Trails said, “During the epidemic, citizens have developed the habit of hiking, but they may not know that they can get access to nature close to home. If more people get to know their backyard trails, it may relieve the burden on overcrowded country park routes.”

The research found that trail accessibility is generally good, but better signage and safer pedestrian facilities are needed near trailheads. The Transport Department should review pedestrian crossing facilities at Fu Yung Shan near the Chuk Lam Sim Monastery and near trailheads on Shum Wan Shan and Ping Shan. Traffic calming measures or a marked pedestrian lane should be implemented on Jat’s Incline at Hammer Hill where hikers share a narrow roadway with light but fast-moving traffic. In order to improve the perceived accessibility of backyard trails, the research team suggested to improve wayfinding signage near trailheads and in nearby MTR stations.

It was also found that while the government had provided amenities such as seating and shade on most of the trails, they were designed and located in a cookie-cutter way and did not necessarily match up with how people used the trails. For example, seats were usually installed at intervals facing the path. However, trail users often placed their own seats in clusters in flat clearings. The Home Affairs Department should conduct public engagement with trail users to ensure that future facilities are designed to better meet users’ needs.

Another major finding was that most of the trails explored by the research team (with the major exception of Sir Cecil’s Ride) had been concretised or stone-paved by the HAD. The over-concretisation of trails has been criticised due to the environmental damage caused by the construction process and the continuing impact on water run-off and soil erosion. The HAD can engage environmental groups in pilot projects to carry out environmentally friendly trail repairs (using natural materials instead of hard paving) on a small scale. Doing so would require cooperation from the Lands Department and should be given support at the bureau level.

This report documented the informal structures that neighbourhood residents have created. In the absence of comprehensive management by the government, people have transformed backyard trails into “common spaces” that are shared and maintained by volunteers. However, while these activities generate community benefits, the construction of informal structures is illegal. Some structures, such as rain shelters, are relatively benign, but others, like makeshift staircases can cause significant environmental damage. However, enforcement by the Lands Department is sporadic and carried out based on complaints rather than on objective assessment of environmental harm or risk to public safety. This also produces an antagonistic relationship between the government and trail users, especially retirees who are the most frequent users of backyard trails.

Carine Lai, Senior Project Manager of WYNG Foundation said, “Backyard trails often fall on green belt land, which is leftover land with an ambiguous planning purpose: it has never been comprehensively managed as an ecological or recreational resource since the land might be repurposed at any time. One major consequence of a lack of comprehensive vision is the neglect of historic structures, with the wartime ruins on Mount Davis and the defunct service reservoir under Woh Chai Shan prior to its attempted demolition in 2021 serving as prime examples.”

She suggested in the medium term, the government should lay the groundwork for an “adopt-a-trail” mode of management. The government can make use of existing mechanisms such as short-term tenancies for nonprofit organisations or government land allocations to regularise informal structures for community use in certain places, ensure that they are adequately maintained, and prevent further uncontrolled construction.

Green belt areas with important heritage structures such as Mount Davis require more intensive management to prevent further damage through neglect and vandalism and to spotlight their educational potential. In this case, the government should establish heritage parks. In the long run the government may need to establish another body under the Culture, Sports and Tourism Bureau to combine expertise in environmental and heritage conservation with recreational planning.